Old Lincoln Highway

This tour will take you back in time via the Old Lincoln Highway – America’s first coast-to-coast highway, established in 1913. Today much of the original grade of this celebrated highway has been paved or surfaced with gravel, but the open spaces of its route through the Laramie Basin remain virtually unchanged from the dawn of history. Crossing this endless prairie from ancient times to the present has always presented both unique challenges and unexpected rewards to the traveler. Only the mode of transportation has changed.

When the Lincoln Highway opened in 1913, no structured highway maintenance system existed, so each county had to take care of its own section with the help of volunteers. Motorists were mostly on their own to find their way along a route that could quickly vanish under heavy snow, thick mud, or spring floods. There was no Wyoming Highway Patrol, no speed limit, and not even a requirement for drivers to be licensed (that didn’t come until 1947). In spite of these challenges – or maybe because of them – the romance of the historic Lincoln Highway lives on.

Tour Menu

Laramie Lincoln Highway History and Photos

About the Maps

Southern Loop

– Abraham Lincoln Memorial Monument

– Tree Rock Detour

– Ames Brothers Monument Detour

– Fort Sanders

Northern Route

– Bosler

– Rock River

Tour Project Credits

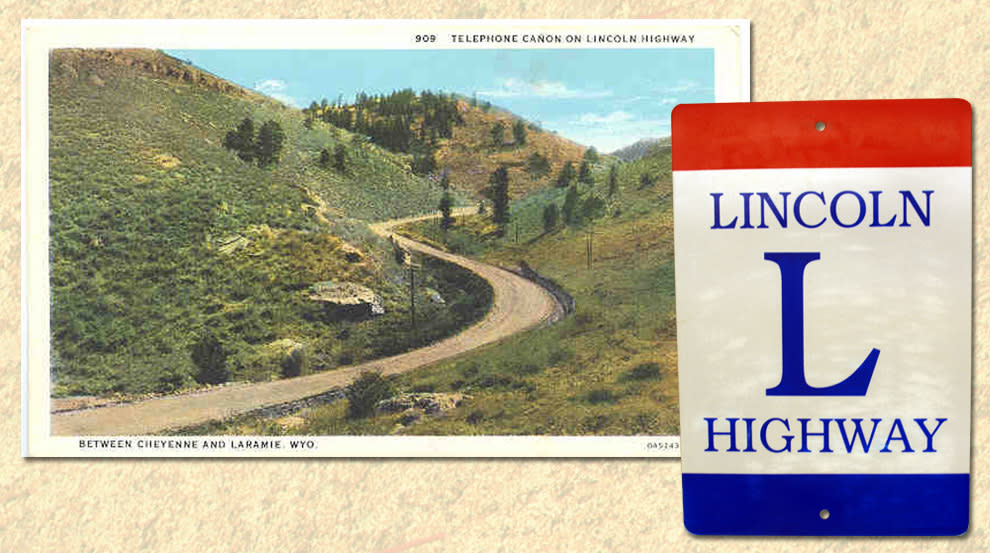

Photo Caption: Old postcard of the Lincoln Highway up Telephone Canyon, east of Laramie.

Photo Credit: www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com, Geoff Dobson, webmaster

Carl Fisher, a developer of the 1906 Indianapolis Speedway, conceived of a coast-to-coast graded road in 1912. A year later the Lincoln Highway Association was formed “to procure the establishment of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful traffic of all description without toll charges…” Henry B. Joy, president of Packard Motor Car Company, was elected president of the association. Other businesses related to the auto industry supported the plan by raising $2 million in the first year. A surprising holdout was Henry Ford, who thought good roads should be a governmental responsibility, not a private enterprise.

The Lincoln Highway Association adopted its red, white and blue logo in 1913. When drivers saw it painted on telegraph poles and fence posts every few miles, they knew that they had not lost the road. As the Lincoln Highway era came to a close in 1928, one of the Association’s last acts was to have Boy Scouts install standardized concrete markers so that the route’s dedication to Abraham Lincoln would not be forgotten. Some of these markers still stand in Wyoming, although most have lost the bronze Lincoln medallion once imbedded in the concrete.

Photo Caption: Henry Joy’s relatives denied his wish to be buried along the Lincoln Highway, but they did erect this monument in his personally chosen spot west of Rawlins in 1936. WYDOT moved it later to the Summit Rest Area. D. Knight Photo, 2008

A Remarkable Inventor

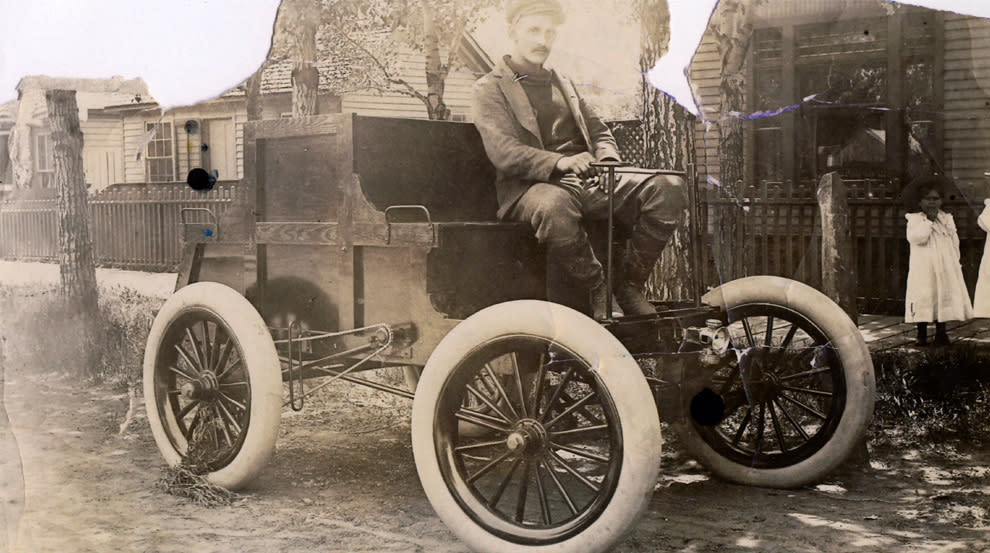

Photo Caption: “Lovejoy 1,” the first horseless carriage in Laramie. Lovejoy is at the wheel, c. 1898.

Photo Credit: the B. Smart Collection, Laramie Plains Museum

Elmer Lovejoy, a prolific Laramie inventor, built the first “horseless carriage” in Wyoming in 1898. During the process, he realized that having the entire front axle swivel like a wagon’s steering mechanism took up too much space and limited speeds. He solved this by inventing a steering knuckle that allowed each wheel to swivel independently of the axle (a mechanism still used in today’s autos). Lovejoy asked his father to help with the $350 needed to apply for a patent but was told, “Go to work. There will never be such a thing as a horseless carriage.” Lovejoy then sold his invention to the Locomobile Company for $800 plus a Locomobile Steamer, and turned to selling Franklin cars from his bicycle shop.

Photo Caption: Lovejoy’s Franklin Service Station, 412-414 S. 2nd St., c. 1920. Note sidewalk-mounted gas pump in center.

Photo Credit: the B. Smart Collection, Laramie Plains Museum

In 1919, Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower was part of an 81-vehicle military convoy that drove the entire 3,250-mile Lincoln Highway. The trip took 62 days and required much rebuilding of bridges along the way. Eisenhower urged the Federal government to make road improvements a priority. Thirty-eight years later, in 1956, then-President Eisenhower signed into law the act funding the Interstate Highway System, initiating the largest public works project in US history.

A Common Predicament

Photo Caption: Seven men attempt to move a car stuck in a mud hole on the Lincoln Highway north of Laramie, c. 1915. Note the spare tire. Photo Credit: the B. Smart Collection, Laramie Plains Museum.

The Lincoln Highway’s route in Albany County changed over the years, and this tour includes sections of the 1913 original road as well as later routes. In 1925, when the Federal government began numbering highways, the Lincoln Highway became U.S. 30 across most of Wyoming. Although locals continued to refer to it as the Lincoln Highway for many years, gradually the name and the Lincoln Highway Association faded away. In 1992, the Association was revived and it now holds conventions and issues a quarterly journal. (http://www.lincolnhighwayassoc.org)

Photo Caption: Laramie men gather with their shovels in front of the Connor Hotel (corner of 3rd St. and Grand Avenue) on September 27, 1913, in response to Governor Carey’s request that “every able-bodied man” in the state do road work that day.

Photo Credit: the L. Zeller Collection, Laramie Plains Museum.

About the Maps

The principal source of the original and later Lincoln Highway routes shown on Maps 2 – 11 is Gregory M. Franzwa, The Lincoln Highway: Wyoming Vol. 3, Patrice Press, Tucson, AZ, 1999. In some cases, these routes were modified based on USGS topographic quadrangles from 1905, 1908 and 1915. Digital base maps and air photos provided by Alan J. Frank, Office of GIS, Albany County, Wyoming, were very helpful to us. Any errors are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Touring The Lincoln Highway

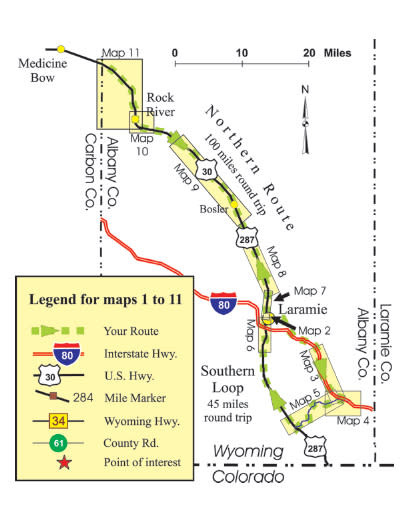

This tour consists of two routes, both of which start in Laramie. The Southern Loop goes east towards Cheyenne and returns to Laramie from the south; the Northern Route heads towards Medicine Bow and then returns on the same road. There are also several optional detours. The total distance for the entire tour, exclusive of detours, is about 145 miles.

Abbreviations

LH = Lincoln Highway

MM = Mile Markers

Southern Loop

Laramie Starting Line

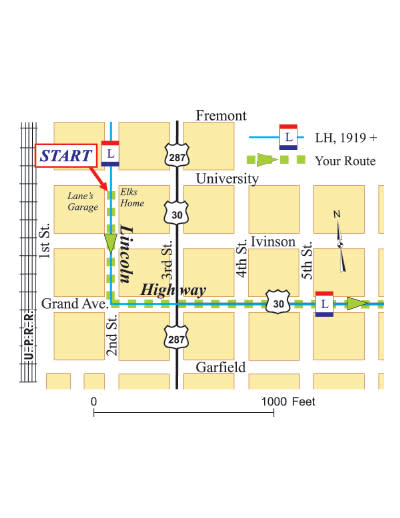

Map 2 – Laramie

Eastbound on the Lincoln Highway (1919 route)

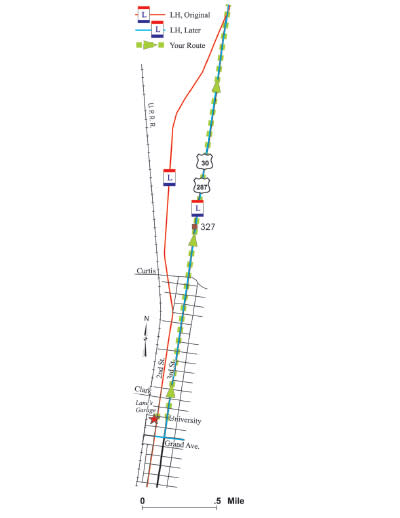

Begin your tour of the Lincoln Highway by heading south on 2nd St. from its intersection with University Avenue. In the 1924 edition of the Lincoln Highway Guide, Lane’s Garage, “Opposite Elks Home”, was the “Control” for Laramie – the place from which distances were measured. Cheyenne was 49.6 miles east and Medicine Bow 56.6 miles north.

Follow the LH route south for two blocks, turning left (east) at Grand Avenue. In the 1920s, the city limits were at the Fairgrounds, then located on the south side of Grand between 18th and 20th Streets.

Continue east to the I-80 interchange, bearing left toward Cheyenne. Ahead, you will pass through a narrow canyon called Telephone Canyon, through which the LH passed starting in 1919. In 1924, the roadway was described as a “boulevard…24 feet wide, surfaced with Sherman gravel” and cost $152,000. A small remnant remains, hugging the canyon cliffs to the north between MM 318 and MM 319.

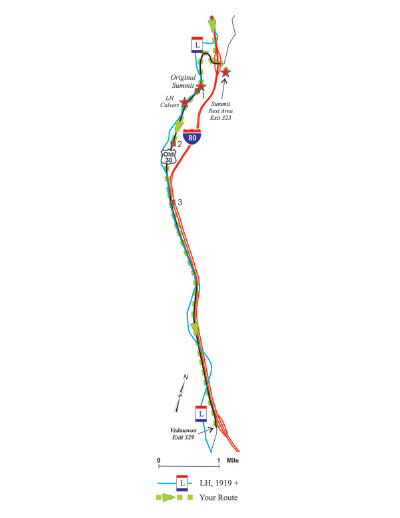

Map 3 – US 30, Summit to I-80 Exit 329

Take Exit 323 and visit the I-80 Summit Rest Area.

Summit Rest Area

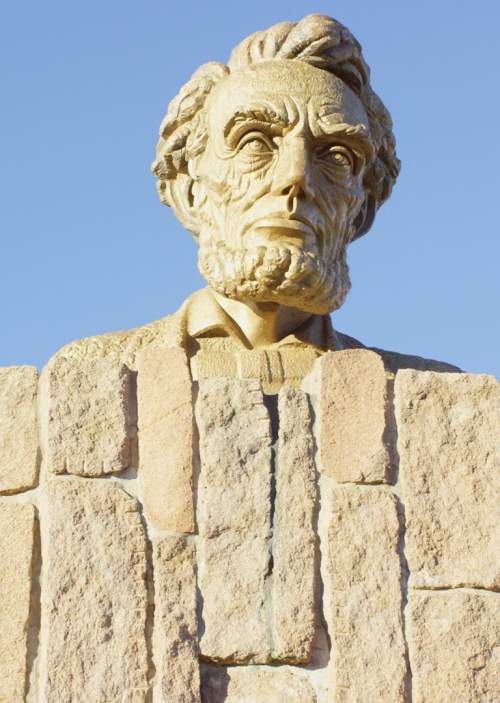

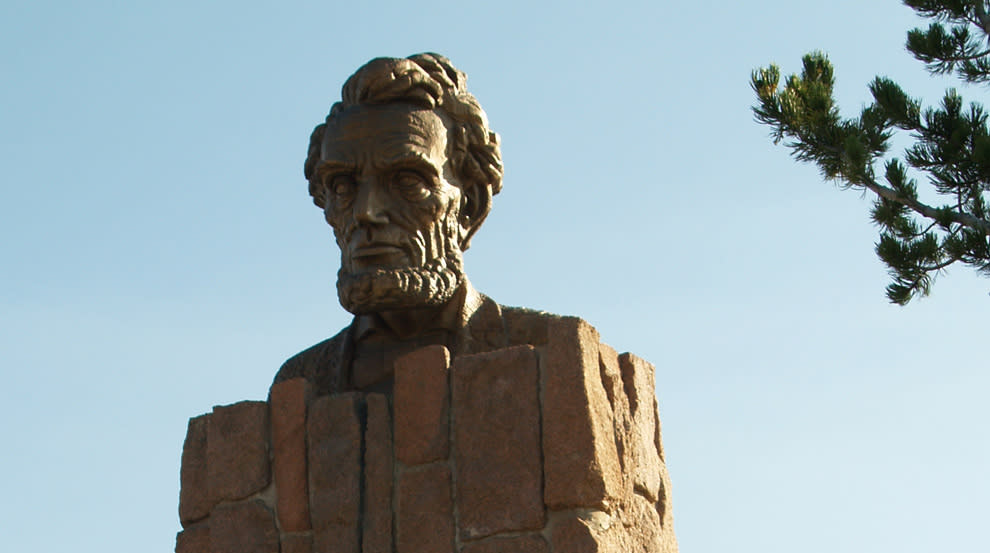

The imposing Abraham Lincoln Memorial Monument was sculpted by University of Wyoming art professor Robert Russin in 1959 to commemorate the highest point on the Lincoln Highway. Look for the Henry Joy monument surrounded by a fence with four Lincoln Highway concrete markers. There are interesting displays inside the building and great views outside.

As you leave the rest area, cross the bridge over I-80 and continue straight up the hill onto old US 30.

Original Summit

The “Lincoln Head” Lincoln Monument was originally here (at 8,835 ft. elevation) on US 30, but was moved in 1968 when I-80 was built. The gravel turnout is on the Lincoln Highway.

A Lincoln Highway stone culvert is down the hill from the Summit and a couple of hundred feet west of old US 30.

Continue on old US 30 to the I-80 Vedauwoo Exit. Bits and pieces of the post-1919 LH roadbed are visible to the right or left, but often you are driving right on top of it.

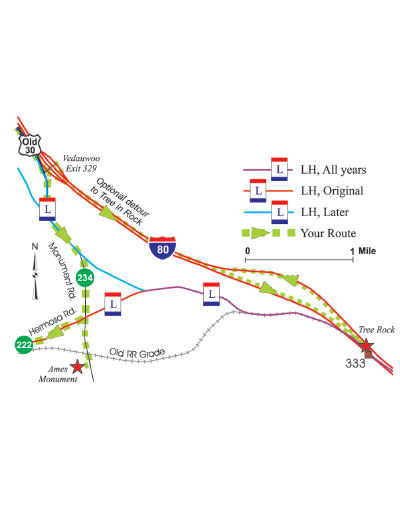

Map 4 – I-80 Exit 329 to Hermosa Road

Tree Rock (8-mile optional detour)

Take I-80 east for four miles to visit this natural landmark which is between the Interstate’s east-west lanes. There is a pull-out where you can safely park, read interpretive signs, and reverse directions to return to the tour.

Take Monument Road south to its intersection with Hermosa Road.

Photo Caption: The old Lincoln Highway (c. 1915) running beside “Tree Rock,” as WYDOT calls it now. This photo was taken in 1955.

Photo Credit: www.wyomingtalesandtrails.com, Geoff Dobson, webmaster

Westbound on the Lincoln Highway (1913 to 1919)

Warning: The first nine miles of this part of the tour are on a gravel road that may not be suitable for some vehicles in the winter due to drifting snow. In this case, return to 2nd and University in Laramie via I-80.

Ames Monument (one-mile optional detour)

Before turning on Hermosa Road, visit the Ames Monument just ahead. The monument marked the highest elevation reached by the transcontinental railroad (8,247 ft.) and was built with local pre-Cambrian Sherman granite, one of the oldest rock types exposed anywhere on earth. In 1868, the Union Pacific Railroad built its main line a few hundred feet to the north, at the foot of the hill where the monument now stands. There was a station, roundhouse and turntable, around which grew the small town of Sherman. When the tracks were relocated around 1901, the little town dried up. Resume the tour by returning to Hermosa Road.

Photo Caption: Ames Monument, the only work of famed architect Henry Hobson Richardson west of the Mississippi River. Photo Credit: R. Bress, 2008.

Hermosa Road

From this vantage point, you can see the Medicine Bow Mountains to the west across the Laramie Basin and the Mummy Range in Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado, to the south.

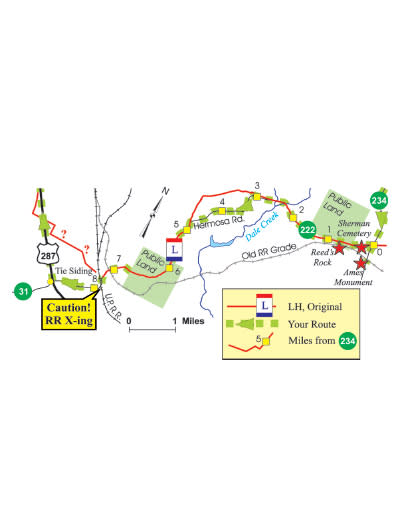

Map 5 – Ames Monument to Tie Siding

Most of the route on Hermosa Road from Monument Road to Tie Siding, about nine miles, is on top of the original Lincoln Highway of 1913, and the gravel road is much like the original with no cuts, fills or other major construction. Look for wildflowers, mule deer, mountain bluebirds and pronghorn antelope while on your journey. Check your odometer as you begin because there are no mile markers along the road.

Soon after starting, note the fenced-in Sherman cemetery to your left.

At about half a mile, you will enter a tract of state land open to the public. This is a good spot to get out and imagine fixing a flat or adding water to the radiator, as if it were 1913. “Reed’s Rock,” the source of granite for Ames Monument, is to the south.

Windswept, high-elevation grasslands occur along most of Hermosa Road. The native plants are well adapted to the cool, dry and short growing season. A dwarf shrub called threetip sagebrush, which never gets more than about 6 inches high, is common. Most trees are limber pine, with flexible branches that withstand strong winds, and are generally grouped on Sherman granite outcroppings. Wyoming big sagebrush grows where winter snow accumulates.

At about 2.5 miles, you cross the Dale Creek flood plain, lined with willows. There are now culverts to keep Hermosa Road reasonably dry, but spring flooding here caused one mud hole after another on the early Lincoln Highway.

At 2.6 miles, cross a cattle guard and note the open range with no fences, much as it was in 1913. Cattle guards confine livestock and avoid the need for frequent gates along the roads.

At 7.7 miles you come to Hermosa railroad crossing. Use great care, as these tracks are the main line of the Union Pacific Railroad and freight trains pass frequently.

Photo Caption: Hermosa Crossing of the Union Pacific. Photo Credit: D.H. Knight, 2008

Tie Siding is a mile farther and here you turn right on US 287 north toward Laramie. Tie Siding, originally just east of the railroad tracks, was established in 1874 and became a railroad loading point for lumber and livestock. It had about 60 residents in 1901.

As you head north from Tie Siding, Boulder Ridge is on the left. Two prehistoric buffalo kill sites have been found on the ridge, along with some of the oldest evidence of human occupation in the Laramie Basin (the Folsom Culture of 12,500 years ago).

The vegetation near Laramie, at 7,200 ft. elevation, is mixed grass prairie. The climate is less rugged in this valley than it is around Ames Monument and many of the plant species are different. As with most grasslands, about 80 percent of the plant biomass is in the soil, so what you see is only a small portion of what is there.

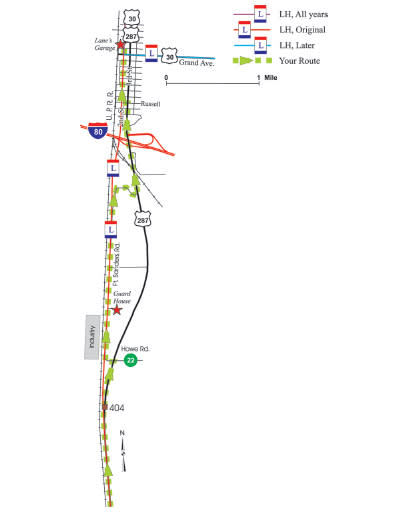

MM 404: The large industrial building on the south is an abandoned WWII government plant built to process local aluminum ore, although the war ended before production was needed. Just north of it is a complex of buildings with the tall smokestacks of an active cement plant, one of Laramie’s largest employers.

From US 287, turn left in front of the cement plant onto Howe Road which quickly turns north and becomes Ft. Sanders Road. This will put you back on the 1913-1919 LH.

Old Guardhouse (1,000-foot optional detour)

After half a mile, turn east (right) onto an unmarked gravel road. About 500 feet down this road is a stone guardhouse from Fort Sanders, which was active from 1866 to 1892. Return to Fort Sanders Road and continue north.

After two miles, you are diverted east, back onto US 287, but the LH continued straight and connected with 2nd St. to the north (see map). In the late 1940s, the new grade for US 287 was constructed east of Fort Sanders Road and joined 3rd St. in Laramie. Continue north on 3rd St. and turn left at the first light onto Russell.

Turn right on 2nd Street. Nearly all of the buildings you see along both sides of this street for the next 10 blocks were here when the Lincoln Highway followed this route.

Laramie

The city was founded in 1868 by the UPRR, which continued as the major employer into the 1960s. With the advent of diesel locomotives that could make longer runs between crew changes and engine servicing, nearly all railroad activities moved from Laramie to Cheyenne. Now, educational institutions, consulting firms and service industries dominate Laramie’s economy.

The Albany County Visitor Center at 800 S 3rd Street (3rd Street and Park Avenue) is a good place to stop for information and guides to other driving and walking tours in Laramie and Albany County.

Northern Route

The second Lincoln Highway tour begins in Laramie and heads north towards Medicine Bow, 57 miles away. You can drive it as a round trip ending back in Laramie, or if you are planning to head further west, you can continue past Medicine Bow for about 37 miles where US 30/287 joins I-80. For the safety of all, please be alert for pronghorn antelope along the road; they are abundant in this part of the Laramie Basin.

Head north on 3rd St. from its intersection with University. This is US 30/287 and also a route of the Lincoln Highway, which followed 3rd St. rather than 2nd St. starting around 1924. At one time there were about 12 filling stations and/or tourist courts in the 15 block stretch of 3rd St. between University Avenue and Curtis Street. The original LH followed 2nd St. north and then veered to the northwest after Lyon St., remaining closer to the tracks for the next couple of miles.

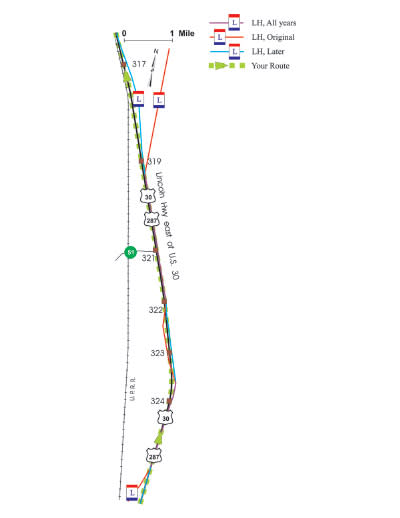

MM 324 to MM 322: Look closely both east and west of US 30/287 to see the old highway’s minimal “borrow pits” – the ditches where dirt is “borrowed” to build up the road grade. Some folks claim that the term is actually “barrow pit” as in “wheelbarrow.” As you continue north, the old roadbed often fades away and then re-emerges.

MM 321 to MM 320: The LH is used as a service road by a subdivision on the east.

MM 320 to MM 319: Watch for a line of telephone poles extending northeast along a private drive atop the original Lincoln Highway.

North of MM 317: Note the wide expanse of prairie dominated by blue grama, western wheatgrass, and fringed sage. This land has never been plowed and most plants are native. Precipitation is low, about 11 inches annually. Sometimes you will spot different kinds of vegetation, such as patches of Wyoming big sagebrush.

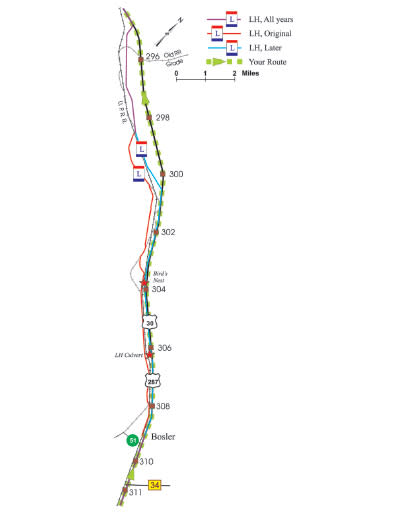

Map 9 – Bosler and north

MP 311: Tom Thorne/Beth Williams Wildlife Research Center (60-mile optional detour)

Here State Highway 34 turns northeast to Wheatland. If you have time for a side trip, this road provides a beautiful drive through Sybille Canyon. About 20 miles from here is the world-famous Tom Thorne/Beth Williams Wildlife Research Center that successfully bred the black-footed ferret in captivity. Once thought to be extinct, they were successfully reintroduced into the wild in places with prairie dog towns large enough to sustain them, and today they number in the hundreds. Usually you can see elk and bison in the enclosures near the research center, but no captive ferrets these days.

Photo Caption: An unidentified driver took a photo of his passengers in this undated photo along the Lincoln Highway.

Photo Credit: the B. Smart Collection, Laramie Plains Museum

MM 309: You are now in Bosler, platted in 1909. Until 1919, most of the town was on the west side of the railroad tracks. The original LH crossed the tracks at this point and remained west of the tracks for the next nine or ten miles to the north; in 1924 it was relocated east of the tracks. Note the former filling station and tourist court. Bosler was a promoter’s dream, with irrigation ditches planned and “fine cabbage farming” recommended. Unfortunately, the dream never materialized.

Photo Caption: Bosler tourist court, a relic along the old LH. Photo Credit: J. Knight photo, 2008.

Just past Bosler, US 30/287 becomes a four-lane, divided highway and heads generally northwest. When the state improved this section in the 1950s, the eastbound lanes were constructed on top of, or adjacent to, much of the 1920’s LH road grade.

MM 306 to MM 301: The post-1924 LH is visible along the fence line between US 30/287 and the railroad.

MM 304: Look for two lone telephone poles with large bird nests on the west side of the highway along the abandoned LH roadbed. At MM 303 there is a depression where standing waters evaporate and leave behind white alkaline deposits where only a few plants can survive. This “gumbo” of wet alkali soil was a nightmare for early motorists (see photo, page 3).

Between MM 301 and 300, a two-track road branches off onto private land to the west – a remnant of the post-1924 LH that is still in use (although travelers must obtain permission first). At about MP 299 the original and later LH routes rejoin, then both disappear beneath US 30/287 near MP 295.

MM 293: Note the ponderosa pines on the sandstone ridge to the south of the highway. Snow-capped Elk Mountain (elevation 11,152 ft.) can be seen to the west.

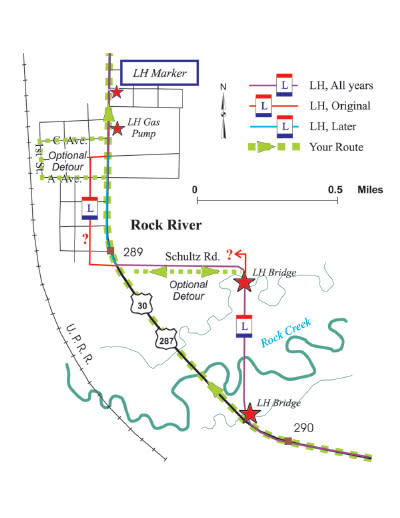

Map 10 – Rock River

MM 290.75: Look to the northeast (right) to see the remains of a concrete bridge over an irrigation ditch; here the LH went north along a fence to another bridge across Rock Creek itself.

Old Rock Creek Bridge (one-mile optional detour)

At the top of the hill on the south edge of Rock River, take a short detour east onto Schultz Road, which ends at a ranch yard. Look to your right at a concrete 1913 LH bridge over an 1882 irrigation ditch. On the other side of that bridge to the south is an alley lined with cottonwood trees where the route of the LH can still be seen as it passed over Rock Creek. The bridge is now gone except for its abutments. Look to the left from the front of the rancher’s house at 1212 Schultz Road. Up the hill to the north, you can still see the route of the original road (it was only used for about one year). Return to US 30/287.

Photo Caption: 1913 LH off Schultz Road, Rock River, now a private ranch road; permission to travel required. Photo Credit: W. Ware, 2008.

Downtown Rock River (optional detour)

Follow Avenue A, 1st St., and Avenue C for a tour of downtown Rock River. An old bank building and an old hotel are along Avenue C. Return along Avenue C to US 30/287 and turn left.

Note the old “Lincoln Highway” gas pump at Hostler’s General Store.

Photo Caption: Lincoln Highway gas pump at Rock River. Photo Credit: J. Hansen, 2008.

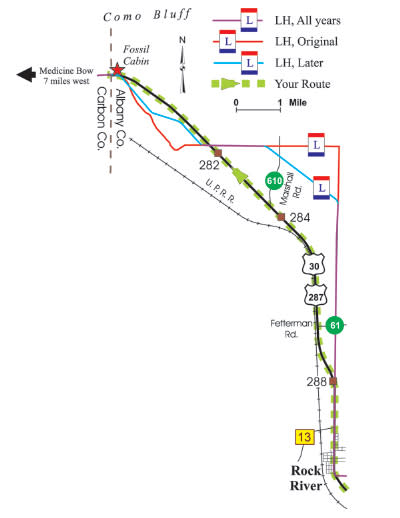

MM 288 to MM 282: Between these mile markers along US 30/287, the original LH went straight north and then turned due west. In the 1920s, a diagonal shortened the LH somewhat, and the modern highway shortens it further. The distance from Laramie to Fossil Cabin along the original Lincoln Highway was 52.7 miles. Later LH routes reduced this to 51.1 miles, and today it is 49.5 miles. That is, today’s route is only about 3 miles shorter than the original – much of the savings occurs between these mileposts.

MM 288: A monument marks the crossing of the old (1863) east/west Fort Halleck to Fort Laramie road. Fort Laramie is about 120 miles east and is a National Historic Site. Established as Fort John in 1834, it was purchased by the US Army in 1849 to protect immigrants along the Oregon/Mormon/California Trails. Fort Halleck was established in 1862 to protect immigrants along the Overland Trail and is not accessible without permission. Laramie Peak, elevation 10,272 ft., is to the northeast.

MM 282: A former gas station along the LH has been turned into a residence. Nearby, the Lincoln Highway crosses US 30/287 and provides an outstanding view of the old roadbed. It crosses again in the vicinity of Fossil Cabin.

Photo Caption: Fossil Cabin, 50 miles northwest of Laramie. Photo Credit: W. Ware, 2008.

MM 279: Fossil Cabin at the Carbon County/Albany County border. Constructed of masonry and dinosaur bones, this cabin is touted as “the world’s oldest building.” Fossils representing many species of dinosaurs were found in 1877 at Como Bluff, the nearby ridge running east/west behind the cabin. Many of the large dinosaur specimens exhibited in museums around the world came from this site. A nearly intact, 75 ft.-long specimen of an Apatosaurus from Como Bluff enthralls visitors at the Geological Museum at the University of Wyoming in Laramie.

The tour ends here. If you return to Laramie, look for portions of the old LH that may be more visible as you drive south. If you continue west, the next major town after Medicine Bow is Rawlins, 58 miles further west.

Medicine Bow (14 mile optional extension)

If you have time, continue seven miles on US 30/287 to the town of Medicine Bow. The old LH runs atop or alongside the current road on the left. Stop at the museum in the former train station where you’ll find a Lincoln Highway marker in front. In 1902, Owen Wister wrote “The Virginian,” set here. It is generally acclaimed as the first novel to establish the laconic cowboy-hero stereotype. The Virginian Hotel across the street was built in 1911 and remains a favorite café and watering hole.

THE TOUR GUIDES PROJECT

The Albany County Historic Preservation Board

Project Coordinator: Larry Ostresh (1942-2013) ACHPB

Editor in Chief: Sarah Perrine, ACHPB

Funding Director: Amy Williamson, ACHPB President

Historical Consultants: Phil Roberts and Judy Knight

Volunteers: Cecily Goldie, Teresa Sherwood, Brandon Bishop,

Jerry Hansen, Mary Humstone, Chavawn Kelley, Sonya Moore,

Tony Parilla, John Waggener, Nancy Weidel

Partners: Albany County Museum Coalition, Albany County Tourism Board,

Laramie Main Street Program, Laramie Plains Museum, Lincoln Community Center

The seven Laramie & Albany County Tour Guides in this series were funded by grants from the Albany County Tourism Board; Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office; University of Wyoming Foundation, Division of Student Affairs, and Art Museum; Cecily Goldie; Judy Knight; Amy M. Lawrence; Amy Williamson; Centennial Valley Historical Association; Edward Jones Investments (Jon Johnson); Laramie Plains Museum; Laramie Railroad Depot Museum; Wyoming Territorial Prison State Historic Site.

These Tour Guides were financed in part with funds granted to the Albany County Historic Preservation Board from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. The Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office administers these federal funds as part of Wyoming’s Certified Local Government program. This program received Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. The contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Dept. of the Interior. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, P.O. Box 37127, Washington, D.C. 20013-7127.

CONTACTS

Wyoming SHPO, http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us

Albany County Tourism Board: www.visitlaramie.org